.

lundi 29 octobre 2018

jeudi 25 octobre 2018

mardi 23 octobre 2018

La Commission européenne rejette le budget italien

Bruxelles tire la sonnette d'alarme mais tente dans le même temps d'éviter une confrontation trop frontale qui pourrait affoler les marchés.

C'est une première dans l'histoire de

l'Union européenne. Ce mardi, la Commission européenne a rejeté le

budget de la coalition populiste au pouvoir en Italie, considérant que ce dernier n'est pas conforme aux règles.

Lors

d'une conférence de presse, le commissaire européen aux Affaires

économiques, Pierre Moscovici a ainsi demandé à l'Italie une révision

dans les trois semaines, comme les textes le prévoient. Dans le cas

contraire, elle se heurte à l'ouverture d'une « procédure pour déficit

excessif », susceptible d'aboutir à des sanctions financières

correspondant, en théorie, à 0,2 % de son PIB (soit 3,4 milliards

d'euros en prenant les chiffres de 2017).

Pas de « retour en arrière »

Avant même l'annonce de la Commission, le vice-Premier ministre italien, Luigi Di Maio, chef de file

du Mouvement 5 étoiles, a indiqué que les « prochaines semaines seront

des semaines de grand dialogue avec l'Europe, les marchés ».

Le ministre italien de l'Intérieur Matteo Salvini a, de son côté, prévenu que l'Italie ne reviendrait « pas en arrière ».

Bruxelles avait déjà pointé du doigt dans un courrier à Rome la

semaine passée le dérapage budgétaire « sans précédent » de l'Italie

depuis les nouvelles règles mises en place en 2013 et le risque de

« non-conformité grave » de son budget avec les règles européennes.

Mais en dépit de ces critiques, le

gouvernement italien avait maintenu lundi ses prévisions. Alors que le

précédent gouvernement de centre gauche avait promis un déficit public

de 0,8 % du PIB en 2019. Dans une lettre que le ministre de l'Economie a fait parvenir à Bruxelles, Rome prévoit désormais d'atteindre 2,4 % l'an prochain, puis 2,1 % en 2020 et 1,8 % en 2021.

« Malheureusement,

les clarifications reçues hier (lundi) n'étaient pas assez

convaincantes pour changer nos précédentes conclusions voulant qu'il y

ait une non-observance particulièrement grave de la recommandation

adressée à l'Italie par le Conseil », a indiqué Valdis Dombrovskis,

vice-président de l'exécutif européen.

Source AFP

À propos du national-socialisme : Réponses aux objections courantes dans nos « milieux »

Il me semble possible de réduire à

quatre les objections qui – dans nos « milieux » (catholiques et

traditionalistes) – sont couramment effectuées à propos du

national-socialisme :

- L’Église a condamné le nazisme ;

- Ce dernier est une idéologie (ce qui est déjà un mal) ;

- C’est même une idéologie de gauche (la preuve en est que les plus grands collaborateurs (Laval en tête) étaient des hommes de gauche) ;

- La doctrine sociale de l’Église est, quoi qu’il en soit, la seule doctrine politique valable.

Je vais tâcher de répondre très brièvement à ces objections.

Première objection : L’Église aurait condamné le national-socialisme

Ceci est inexact. La fameuse encyclique Mit Brennender Sorge ne condamne pas le national-socialisme (et c’est précisément ce que démontre le petit livre de Pierre Maximin, Une encyclique singulière sous le III° Reich que vous pouvez acquérir ici).

En effet :

L’encyclique se propose pour fin

d’analyser « la situation de l’Église Catholique dans le Reich

Allemand » (« situation » dont l’Église estimait apparemment à avoir à

se plaindre, comme d’ailleurs de toutes les « situations » qui lui sont

accordées depuis la Réforme), et non d’étudier, ou encore moins de condamner, une quelconque doctrine politique.

De plus, Pie XI, s’il critique

implicitement le régime national-socialiste, qui – comme tout régime

politique – avait ses déviances, ne condamne à aucun moment de l’encyclique le national-socialisme en tant que tel.

D’ailleurs, le terme

« national-socialisme » n’apparaît pas une seule fois dans le texte

pontifical ; certes, Pie XI y fait allusion ; mais comment pourrait-il

condamner une doctrine sans la nommer ? (Pascendi parle explicitement du « modernisme », idem pour Divini Redemptoris avec le « communisme athée qui est intrinsèquement pervers », etc…).

Pierre Maximin, Une encyclique singulière sous le III° Reich

Deuxième objection : Le national-socialisme serait une idéologie

Si par idéologie on entend

doctrine politique, alors, oui, le national-socialisme est une doctrine

politique, et il me semble qu’il n’y rien de mal à cela (et je ne fais

pas mienne la théorie « jeandominicaine » d’après laquelle toutes les

doctrines en « isme » seraient par nature mauvaises).

Mais si, toujours par ce mot d’idéologie,

on entend une doctrine politique fondée non pas sur le réel mais sur un

système d’idées a priori, et voulant s’imposer au réel, alors il me

semble que le national-socialisme (celui de Hitler, tel qu’il est exposé

dans Mein Kampf – et non celui vendu par les vainqueurs hollywoodiens) n’est pas une idéologie, mais une doctrine bien fondée sur le réel : mise en valeur de la nation (qui est une réalité, et une chose légitime – comme le rappelle justement Pie XI dans son encyclique) ; primat

de la société politique sur les corps intermédiaires et la famille,

tout en réaffirmant l’importance de ces mêmes corps intermédiaires (les « communautés d’entreprises » bénéficiaient d’une certaine autonomie sous le régime national-socialiste) et de la famille patriarcale (le père de famille avait un rôle majeur) ; État autoritaire, parce qu’ayant pour finalité d’élever la nation, de la faire parvenir au Bien Commun ; primat absolu du Bien Commun sur le bien individuel, sans pour autant nier ce dernier ; etc…

Le national-socialisme n’est donc pas, me semble-t-il, une idéologie (au mauvais sens du terme), mais une doctrine réaliste.

On pourrait, il est vrai, reprocher deux

choses au régime qui a mis en pratique cette doctrine : d’une part un

racisme trop matérialiste – en l’occurrence l’aryanisme –, et d’autre

part l’eugénisme (deux choses qui vont assez logiquement de pair).

Mais ces deux éléments ne faisaient pas partie de l’essence même du national-socialisme ; ils s’apparentent plutôt à des déviances, certes graves, mais accidentelles.

D’ailleurs, seule une minorité des

membres du NSDAP, tel que Rosenberg par exemple avec son pamphlet

anti-catholique, croyait vraiment en l’aryanisme et était favorable à

l’eugénisme ; et comme le fit remarquer Degrelle dans Hitler pour mille ans, de telles absurdités n’auraient de toute manière pas pu faire long feu.

Il faut également préciser que Goebbels qualifiait l’ouvrage Le mythe du vingtième siècle de Rosenberg de « rot idéologique » et qu’Hitler lui-même a affirmait en 1936 dans un discours à Munich que :

Le livre de Rosenberg n’est pas une publication officielle du Parti. Au surplus, je vous affirme que l’Église catholique possède une force vitale qui se prolongera au delà de notre vie à nous tous réunis ici.

Léon Degrelle – Hitler pour 1000 ans

Troisième objection : Le national-socialisme serait une idéologie de gauche

Là aussi, cela me semble totalement contestable.

En effet, le national-socialisme est essentiellement mono-archiste et nationaliste, élitiste et organiciste (est dite organiciste

la doctrine politique favorable à une société organique, c’est-à-dire à

une société dans laquelle tout citoyen participe d’une manière ou d’une

autre à la poursuite active du Bien Commun, et se voit récompensé en

fonction de son engagement) ; mais c’est là, précisément, la définition

du fascisme (au sens le plus général du terme) ; le national-socialisme n’est donc qu’une individuation, qu’une particularisation, du fascisme, « à la mode » germanique.

Or, le fascisme est, pour reprendre les mots de Joseph Mérel, « une

tentative européenne, personnalisée par le génie des nations qui ont

essayé de le promouvoir, de refonder l’ordre d’Ancien Régime –

c’est-à-dire l’ordre européen avant la Révolution de 1789, – mais en

évitant de reproduire les travers qui ont précipité sa chute » (Fascisme et Monarchie commandable ici) ; or est dite de droite toute doctrine politique fondée sur les valeurs traditionnelles (et de gauche toute doctrine politique hostile à ces valeurs traditionnelles, c’est-à-dire en révolte contre elles).

Par conséquent, il me paraît

évidement juste de dire que le fascisme, et ainsi le

national-socialisme, sont des doctrines de droite.

Le terme de « socialisme » est, je le

concède, équivoque et donc maladroit ; mais il me semble que, dans le

cas présent, il ne signifie rien de plus qu’ « organicisme », rien

d’autre que la recherche d’une organisation politique, sociale et économique plus juste, c’est-à-dire plus conforme à la justice distributive, – par-là opposée à la fois au capitalisme et au communisme.

Voici d’ailleurs ce que le Duce Mussolini pouvait écrire du socialisme :

Le socialisme, une fois frappé dans ces deux principes fondamentaux de sa doctrine, il n’en reste plus que l’aspiration sentimentale – vieille comme l’humanité – à un régime social dans lequel doivent être soulagés les souffrances et les douleurs des plus humbles.

Sur ce sujet précis également – entre

Hitler et le socialisme – nous pouvons retrouver les écrits de

l’historien Hajo Holborn dans son ouvrage A history of modern Germany 1840-1956 :

Il n’a jamais été socialiste. Dans un de ses discours en 1927 qu’a organisé le magnat de la Ruhr Emil Kirdorf (1847-1938) devant des industriels, Hitler déclare : « Le plus grand nationalisme est essentiellement identique avec les plus grandes préoccupations du peuple et le plus grand socialisme est identique à la forme la plus élevée de l’amour du peuple et de la patrie. » Le socialisme et le nationalisme étaient pour lui des termes interchangeables qui changeaient en fonction du groupe social auquel il s’adressait.

Et c’est probablement parce que le

régime national-socialiste était radicalement à droite, ainsi opposée au

Nouvel Ordre Mondial, et parce qu’il était le seul, dans les faits, à

pouvoir lutter efficacement contre lui, que gangsters américains et

barbares slaves se sont unis pour le détruire, non seulement politiquement – par la guerre – mais aussi et surtout spirituellement,

c’est-à-dire dans les esprits – par le plus grand mensonge historique

qu’ait jamais connu l’humanité (inutile de préciser : tout le monde aura

compris).

Mais certains diront que les plus grands

collaborateurs (Laval en tête) étaient des hommes de gauche – ce qui

prouverait que le national-socialisme est une doctrine de gauche.

Or, une fois de plus, c’est historiquement inexact.

D’abord, Laval n’a pas collaboré par

conviction mais par opportunisme (il n’a d’ailleurs jamais tenu de

propos favorables au national-socialisme en tant que tel).

En revanche, ceux qui ont collaboré par conviction, eux, étaient fascistes et donc de droite.

Je pense notamment à des partis tels que

le Rassemblement National Populaire (Déat), le Parti Populaire Français

(Doriot), ou le Parti Franciste (Bucard) ; je pense aussi à des

écrivains tels qu’Abel Bonnard, Brasillach, Céline, Alphonse de

Châteaubriant, Cousteau, Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, Montherlant, etc..

Tous ces gens-là étaient profondément à droite.

Il est vrai qu’un certain nombre d’entre

eux sont passés par la gauche ; mais ils n’en sont pas pour autant

blâmables : au contraire, je crois qu’on peut les féliciter d’avoir

compris que le socialo-communisme ne se différenciait par réellement du

capitalisme, mais que la seule doctrine (politique, j’entends)

réellement opposée à celui-ci, dans les années 30, était le fascisme.

Fascisme et Monarchie – Jospeh Merel

Quatrième objection : La doctrine sociale de l’Église serait, quoi qu’il en soit, la seule doctrine politique valable

Sujet délicat… Je me contenterai de faire remarquer les choses suivantes :

Tout d’abord, cette doctrine n’est pas politique, mais sociale, c’est-à-dire

qu’elle n’a pas pour objectif de s’occuper de la vie de la société

politique en tant que telle, mais plutôt de guider les personnes dans

leur conduite en société, dans leurs rapports avec les autres ; or,

contrairement à ce que beaucoup pensent, le politique ne se réduit pas

au social (c’est d’ailleurs l’une des erreurs communes à la fois aux

surnaturalistes et aux modernistes) ; on ne peut donc considérer la doctrine sociale de l’Église comme une doctrine politique.

Par ailleurs, même si l’on considère que

la doctrine sociale de l’Église pose certains principes, ou fondements,

de la vie politique, il n’en demeure pas moins que ces principes

doivent ensuite être individués dans les société concrètes ; il

est donc normal, me semble-t-il, de trouver des doctrines politiques

diverses (bien qu’elles doivent toutes répondre aux mêmes principes).

En outre, de même que l’existence de Dieu ou l’immortalité de l’âme ne sont pas essentiellement des

vérités de Foi mais des vérités rationnelles confirmées par la

Révélation, la doctrine sociale réaliste (c’est-à-dire celle qui est

conforme au réel) n’est pas essentiellement la doctrine sociale

de l’Église ; mais elle est celle de l’Église dans la mesure où cette

dernière l’a fait sienne, parce que réaliste ; plutôt que de parler

de « doctrine sociale de l’Église », parlons donc plutôt de doctrine sociale réaliste ;

Enfin, j’ajouterai que si « l’Église n’a

besoin ni du socialisme, ni du nazisme, pour établir une doctrine

sociale » (j’ai souvent entendu cela…), les laïcs n’ont pas attendu

l’Église pour en établir une : le domaine social et politique est, et

demeure, celui des laïcs – en tant que laïcs (même si les clercs peuvent

aussi – naturellement – donner leur opinion).

(Et pour être tout-à-fait exact, il nous

faudrait rappeler que la doctrine sociale de l’Église, du moins celle

qu’ont développée les Papes depuis Léon XIII, contient un grand nombre

d’imprécisions, voire d’erreurs (confusion entre le social et le

politique, mauvaise conception du principe de subsidiarité, promotion

d’une « démocratie chrétienne », personnalisme maritanisant,

droit-de-l’hommisme » diffus, etc…) ; mais un développement sur ce sujet

serait ici trop long et devrait faire l’objet d’un autre article).

Pour conclure, j’ajouterai que seules

l’Allemagne national-socialiste et ses alliées (l’Italie et la Hongrie

fascistes) étaient à la fois opposées au communisme (ce qui n’était le

cas ni des États-Unis, ni de l’Angleterre et ni de la France

malheureusement…) et concrètement en mesure de s’opposer à la montée en

puissance de l’URSS (ce qui était impossible à des pays tels que

l’Espagne ou le Portugal) ; seul le régime national-socialiste était capable de défendre ce qu’il restait encore de la chrétienté ; et c’est ce qu’avait compris un certain Mgr Mayol de Lupé :

Le monde doit choisir : D’un côté la sauvagerie bolchevique, une force infernale ; de l’autre la civilisation chrétienne. Nous devons choisir à tout prix. Nous ne pouvons loyalement rester neutres plus longtemps ! C’est l’anarchie bolchevique ou l’ordre Chrétien !

C’est également ce qu’avait compris de

fervents catholiques tels que Léon Degrelle ; ou encore Adrien Arcand

(nous vous conseillons l’excellent ouvrage Serviam qu’on peut se procurer ici

sur les écrits d’Arcand); c’est, je crois, ce qu’aurait dû comprendre

tous les catholiques, et ce que – malheureusement – ils n’ont pas

compris.

Réveillons-nous ! Deus Vult.

Louis Le Lorrain

Pour aller plus loin dans le réveil :

- En vidéo sur l’alliance du fascisme et de la monarchie par Merel -> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Axj0peOiQ0

- En vidéo sur la défaire de l’Europe Chrétienne en 1945 par Degrelle -> https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NVg-IWo-q50

- Sur la démocratie -> https://deus-vult.org/actualites/pour-en-finir-totalement-avec-la-democratie/

- Sur le totalitarisme du Bien Commun de l’abbé Meinvielle -> https://deus-vult.org/actualites/conception-catholique-de-la-politique-abbe-meinvielle/

- Sur la fameuse encyclique Mit Brennender Sorge -> https://deus-vult.org/actualites/mit-brennender-sorge-et-le-iiie-reich/

- Le Duce Mussolini sur le socialisme -> https://deus-vult.org/actualites/fascisme-mort-du-socialisme-et-naissance-du-corporatisme-detat/

- Sur l’importance capitale du racisme en tant que catholique -> https://deus-vult.org/actualites/racisme-et-catholicisme/

- Deus Vult

lundi 22 octobre 2018

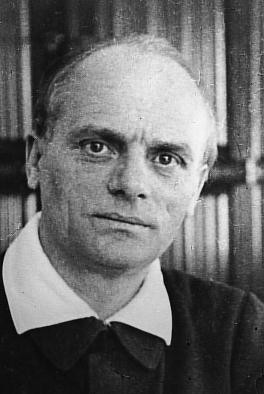

Robert Faurisson a rejoint la Maison du Père

Le

professeur Robert Faurisson est décédé dimanche 21 octobre 2018 vers 19

heures à Vichy au retour d’un voyage à son lieu de naissance à

Shepperton (Royaume-Uni). Il avait 89 ans.

Né

près de Londres, le 25 janvier 1929, de père français et de mère

britannique (d’origine écossaise), le professeur Robert Faurisson a

successivement enseigné d’abord le français, le latin et le grec, puis

la littérature française moderne et contemporaine et, enfin, la

« critique de textes et documents (littérature, histoire, médias) ». Il a

notamment enseigné à la Sorbonne, puis dans une université de Lyon.

À

la suite de la publication du résultat de ses recherches, le droit

d’enseigner lui a été retiré. Il a commencé à faire connaître le

résultat de ses recherches surtout à partir de 1978-1979 dans deux

articles du journal Le Monde où

il a en particulier fait état de sa connaissance des plans des

crématoires d’Auschwitz et de Birkenau (qui étaient jusque-là tenus

cachés et qu’il a découverts le 19 mars 1976) ainsi que de, selon lui

l’impossibilité physico-chimique du fonctionnement de chambres à gaz

homicides dans les camps de concentration allemands. Le 17 décembre

1980, à la station de radio Europe 1, il a résumé son révisionnisme en

une phrase de près de soixante mots :

Les prétendues chambres à gaz hitlériennes et le prétendu génocide des juifs forment un seul et même mensonge historique, qui a permis une gigantesque escroquerie politico-financière dont les principaux bénéficiaires sont l’État d’Israël et le sionisme international et dont les principales victimes sont le peuple allemand – mais non pas ses dirigeants – et le peuple palestinien tout entier.

De

1978 à 1993, Robert Faurisson a subi dix agressions physiques. De 1981 à

ce jour il a été très souvent condamné en justice mais jamais à une

peine de prison ferme. Le 13 juillet 1990, dans l’espoir de le faire

taire, une loi spéciale a été adoptée par la France contre le

révisionnisme ; cette loi est appelée soit « loi Faurisson », soit « loi

Fabius-Gayssot », du nom de son promoteur, Laurent Fabius, député

socialiste, richissime, d’origine juive, et du nom de son signataire

principal, le député communiste Jean-Claude Gayssot.

Robert Faurisson est l’auteur d’une dizaine d’ouvrages en français, dont des Écrits révisionnistesrassemblés en six volumes.

Paix à son âme.

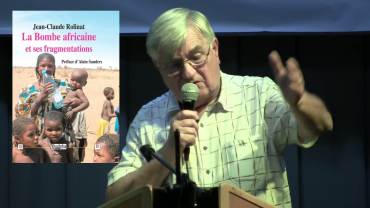

JeanClaude Rolinat présente son livre "La bombe africaine et ses fragmentations" (Dualpha)

Entretien avec Jean-Claude Rolinat, auteur de La Bombe africaine et ses fragmentations, préfacé par Alain Sanders (éditions Dualpha), publié sur le site de la réinformation européenne EuroLibertés (propos recueillis par Fabrice Dutilleul).

L’Afrique, une bombe ? Vraiment ?

Nous

sommes face à une menace mortelle qui n’a jamais eu d’équivalent ; rien

à voir avec les « grandes invasions » post-Empire romain de nos manuels

scolaires ! C’est une épée de Damoclès qui plane sur nos têtes. Les

premiers coups sont ces vagues d’immigrants qui, sans cesse, labourent

les plages d’Europe, du détroit de Gibraltar aux archipels grecs. Des

docteurs Folamour trahissent leurs concitoyens en facilitant un

phénomène « d’invasion/immigration ». Même des ecclésiastiques

travestissent et dévoient le message de l’Église, complices en cela du

milliardaire George Soros qui est dans tous les mauvais coups portés

contre la civilisation européenne. Des ONG type « SOS Méditerranée »

veulent absolument nous culpabiliser. Serions-nous donc des « sans cœur

», nous qui sommes conscients des conséquences de tout cela ? Et ça

marche auprès de certains. Il n’est que de voir ces retraités, par

ailleurs bien ponctionnés par Macron, s’affairer autour de marmites type

soupe populaire, afin de nourrir les « migrants », pour qui ils ont

benoîtement les yeux de Chimène !

Soyez plus précis : cette bombe, c’est quoi ?

Cette

bombe n’est ni sexuelle, ni atomique, ni numérique, elle est

DÉMOGRAPHIQUE ! L’Afrique est une usine humaine incroyablement

prolifique. Jugez-en : en 1900, 100 millions d’habitants, l’homme blanc

arrive avec ses médecins coloniaux. Petit à petit, ils vont éradiquer

les grandes endémies, en 1990, le continent compte 640 millions de

personnes, six fois plus en 90 ans ; il y a trois ans, en 2015, c’était

déjà 1 milliard d’êtres humains, presque le double en 25 ans ! Nous

sommes partis pour, excusez du peu ! 4 milliards 400 millions en 2100 !

C’est proprement invivable. Et pour eux ! Et pour nous ! Le Nigéria, par

exemple, ce colosse aux pieds d’argile de l’Afrique de l’ouest, au bord

de l’éclatement entre musulmans au Nord et chrétiens et animistes au

Sud, aura 400 millions d’âmes à la fin du siècle, contre 190/200 de nos

jours !

Les ressources alimentaires vont être un problème, sinon LE problème ?

L’écologiste

René Dumont avait tiré la sonnette d’alarmes dans les années 1960,

l’année de presque toutes les indépendances, et celle de la tragicomédie

congolaise, dans un ouvrage intitulé L’Afrique noire est mal partie.

Il est toujours d’actualité. Ses théories ont été renforcées par un

autre livre paru chez Plon en 1976. Il disait, en gros, qu’une forte

croissance démographique annulerait les progrès en agriculture et que la

déforestation serait une catastrophe. Et comme si ces catastrophes

parfois incontrôlables ne suffisaient pas, les gouvernements noirs, par

idéologie, par vengeance et par « racialisme » pour ne pas dire plus –

la haine du « Blanc » peut-être ? –, engendrent eux-mêmes des

catastrophes économiques comme au Zimbabwe, l’ex-Rhodésie. Il faut se

rappeler que la Rhodésie nourrissait non seulement son peuple, mais

qu’elle exportait viande, tabac, maïs au lieu de les importer !

L’Afrique du Sud voisine du Président Cyril Ramaphosa, sous l’influence

du raciste Julius Malema de son parti Economic freedom fighters (EFF),

veut exproprier sans indemnité les quelque 40 000 fermiers afrikaners

qui s’accrochent à leur terre ! C’est Ubu roi ! Ils vont faire « crever »

ce pays déjà en complète récession. Rappelons qu’à l’arrivée de leurs

descendants, il n’y avait pas un seul Noir dans cette partie du

sous-continent, seulement quelques tribus d’aborigènes Hottentots, et

des bushmen, comme ceux qui jouent dans le film comique, Les Dieux sont tombés sur la tête.

Pouvez-vous nous donner quelques exemples chiffrés de la catastrophe démographique que vous prédisez ?

S’il

fallait ne retenir que quelques chiffres, ce sont ceux des indices

synthétiques de fécondité du Niger par exemple, 7 enfants par femme, que

même un Macron stigmatisait lors de son discours de Ouagadougou en

novembre 2017 ; 6,06 au Mali, où nos soldats font le boulot que ne

veulent pas faire ces jeunes qui fuient leur pays et qui inondent la

France de leur masse migratoire ; 5,86 au Burkina Faso ; 5,31 de moyenne

en Afrique du Sud alors que les femmes blanches qui sont restées dans

leur pays, menacées de mort et de viols, n’en étaient qu’à 1,4 il y a

dix ans, moins sans doute encore aujourd’hui, mais comme on les comprend

: qui voudrait enfanter dans le beau pays « Arc-en-ciel » de feu Nelson

Mandela, qui fut le plus développé, et de loin, de tous les pays du

continent ?

Plus précisément, qu’elle est la situation en France ?

En

France, ne nous faisons pas d’illusions : un tiers des naissances,

grosso modo, sont le fait d’immigrés récents ou d’immigrés de deuxième

ou troisième génération, dont beaucoup sont « francisés », tout au moins

sur le papier. Nous n’avons qu’à observer les chiffres de la

drépanocytose – une maladie du sang qui ne touche que les Africains, les

Antillais ou les méditerranéens du Sud pour, par décantation –, avoir

forcément une petite idée du panorama démographique français…

La Bombe africaine et ses fragmentations, de

Jean-Claude Rolinat, préface d’Alain Sanders, éditions Dualpha,

collection « Vérités Pour L’Histoire », dirigée par Philippe Randa, 570

pages, 37 euros cliquez ici.

L'intervention de Jean-Claude Rolinat à la 12e Journée de Synthèse nationale (Rungis, 14 octobre 2018 cliquez ici)

dimanche 21 octobre 2018

Les deux grandes dérives du capitalisme mondial

Le poids des monopoles et la financiarisation croissante des entreprises expliquent les dysfonctionnements de l'économie mondiale et du commerce international.

Rappelez-vous. Au début des années 2000, le débat fait rage autour d'un éventuel démantèlement de Microsoft. En situation de monopole avec Windows, système d'exploitation des ordinateurs personnels, il est accusé de pratiques commerciales abusives. La justice américaine réfléchit à scinder l'entreprise en deux. Après une longue bataille judiciaire, Microsoft échappe à la scission .La concurrence en débat

Aujourd'hui, le débat resurgit avec l'apparition des géants du numérique Apple, Amazon, Google et Facebook

(Gafa). En avril dernier, à Washington, au siège du Fonds monétaire

international (FMI), Christine Lagarde, sa directrice générale, s'alarme

de leur taille et de leur pouvoir grandissant. Les Gafa risquent d'étouffer la concurrence et l'innovation essentielles à la croissance de la productivité et à la prospérité mondiales. « La

concurrence est nécessaire. S'il y a trop de concentration, trop de

pouvoir de marché entre les mains de trop peu, cela ne sert à rien à

moyen et à long terme, ni à l'économie, ni au bien-être des individus »,

clame-t-elle. A l'heure des interrogations autour de l'accroissement

des inégalités, de la montée des mouvements populistes, d'une croissance

économique mondiale qui ne profite pas à tous, d'un commerce

déséquilibré, économistes et politiques phosphorent sur les causes de

ces excès et dérives.

La question

concurrentielle ne s'applique pas aux seuls géants du numérique. Mais à

l'ensemble de l'organisation du système productif international des

entreprises.

Quand Donald Trump fustige la Chine

comme responsable des destructions d'emplois aux Etats-Unis, il révèle

l'un des symptômes d'un dysfonctionnement du commerce mondial et de la

mondialisation. Eriger des barrières protectionnistes par une hausse des

droits de douane pour rééquilibrer les échanges n'est pas la bonne

solution. Elle est ailleurs. Dans une réforme et non dans une

destruction d'un capitalisme souffrant de deux dérives.

Concentration du marché des exportations

Dans un rapport paru le 26 septembre, la Conférence des Nations-Unies sur le commerce et le développement (Cnuced) souligne que « l'hyperglobalisation... est régie par de grandes entreprises qui ont acquis une position de plus en plus dominante sur le marché ». Dans le cercle des entreprises exportatrices, 1 % d'entre elles est responsable, en moyenne, de 57 % des exportations d'un pays donné selon les statistiques de 2014. Les 5 % des entreprises les plus tournées vers l'étranger monopolisent 80 % des exportations.

Ce qui est plus inquiétant, c'est que les

nouveaux entrants sur un marché donné - en général des petites PME

exportatrices - ont un taux de survie très faible. En moyenne, 73 % des

entreprises cessent leurs exportations au bout de deux ans. Une

disparition qui ne serait pas liée à une concurrence féroce sur les

marchés mais plutôt au syndrome du « winner takes the most » selon la

Cnuced. Bref à la position dominante de certains mastodontes.

La loi du plus fort

« Il se peut que l'intégration commerciale ait contribué au déclin de la part du travail dans la valeur ajoutée

en instaurant une dynamique qui voit le vainqueur se tailler la part du

lion (« winner takes most ») et en renforçant la concentration du

marché dans un certain nombre de secteurs, avec pour conséquence une

hausse de la part des bénéfices », avance pour sa part l'OCDE dans ses perspectives économiques

. Et de poursuivre : les réglementations favorables aux entreprises en

place, l'absence de politique rigoureuse en matière de concurrence et

une optimisation fiscale agressive peuvent conduire à un accroissement

des bénéfices des entreprises lorsque la concentration du marché

augmente. Un excès que dénonçait déjà en 1776 l'économiste Adam Smith

dans son ouvrage « De la richesse des Nations ». « Il faut toujours

s'opposer à la restriction de la concurrence car elle permet aux

marchands, par l'élévation de leurs profits au-dessus de ce qu'il serait

naturel, de prélever, à leur avantage, un impôt absurde sur le reste de

leurs concitoyens », alertait-il.

Financiarisation croissante

Les

deux organisations internationales mettent aussi toutes les deux en

exergue ce second biais du capitalisme : sa financiarisation croissante

et un tropisme en faveur de la valeur actionnariale des entreprises. « Les

entreprises transnationales ont renforcé leur capacité à opérer à

l'échelle mondiale par le biais de fusions et d'acquisitions renforçant

ainsi leur contrôle sur les concurrents potentiels. Le poids accru des

finances dans leurs opérations est allé de pair avec une stratégie

d'entreprise visant à maximiser la valeur pour les actionnaires », relève la Cnuced. L'exemple d'Apple est révélateur

. En 2013, la firme dispose d'une grosse réserve de cash (145 milliards

de dollars) dont une grande partie hors du territoire américain. Elle

préfère lever sur le marché obligataire 17 milliards de dollars pour financer une partie des 100 milliards de dollars de dividendes et de rachat d'actions promis à ses actionnaires. Le rapatriement d'une partie de ce cash l'aurait obligée en effet à s'acquitter de 35 % de taxes..

Trajectoire insoutenable

« La financiarisation des entreprises a déplacé le pouvoir

décisionnel en faveur des actionnaires. La gouvernance des entreprises

sous l'influence de la finance est le principe de la valeur

actionnariale », observe aussi Michel Aglietta dans une vaste étude

sur le thème « Transformer le régime de croissance » publiée début

octobre. Résultat de cette financiarisation : un affaiblissement de

l'accumulation nette du capital productif. Pour l'économiste, « le

capitalisme financiarisé a déployé un régime de croissance qui évolue

sur une trajectoire insoutenable face aux défis de ce siècle ». Et

ce régime de croissance pose des problèmes plus profonds : montée des

inégalités sociales, concentration de pouvoir et de richesse vers les

plus favorisés et multiplication des rivalités géopolitiques. Le débat

risque de durer et les leaders politiques vont se gratter longtemps la

tête sur les moyens de remédier à ces deux dérives.

Richard Hiault

samedi 20 octobre 2018

WIRTH, Herman (1885-1981)

Hermann Wirth

Robert STEUCKERS:

WIRTH, Herman (1885-1981)

Né le 6 mai 1885 à Utrecht aux Pays-Bas, Herman Wirth étudie la philologie néerlandaise, la philologie germanique, l'ethnologie, l'histoire et la musicologie aux universités d'Utrecht, de Leipzig et de Bâle. Son premier poste universitaire est une chaire de philologie néerlandaise à Berlin qu'il occupe de 1909 à 1919. Il enseigne à Bruxelles en 1917/18 et y appuie l'activisme flamand germanophile. Séduit par le mouvement de jeunesse contestataire et anarchisant d'avant 1914, le célèbre Wandervogel, il tente de lancer l'idée aux Pays-Bas à partir de 1920, sous l'appelation de Dietse Trekvogel (Oiseaux migrateurs thiois). En 1921, il entame ses études sur les symboles et l'art populaire en traitant des uleborden, les poutres à décoration animalière des pignons des vieilles fermes frisonnes. Convaincu de la profonde signification symbolique des motifs décoratifs traditionnels ornant les pignons, façades, objets usuels, pains et pâtisseries, Wirth mène une enquête serrée, interrogeant les vieux paysans encore dépositaires des traditions orales. Il tire la conclusion que les symboles géométriques simples remontent à la préhistoire et constituent le premier langage graphique de l'homme, objet d'une science qu'il appelle à approfondir: la paléo-épigraphie. Le symbole est une trace plus sûre que le mythe car il demeure constant à travers les siècles et les millénaires, tandis que le mythe subit au fil des temps quantités de distorsions. En posant cette affirmation, Wirth énonce une thèse sur la naissance des alphabets. Les signes alphabétiques dérivent, selon Wirth, de symboles désignant les mouvements des astres. Vu leur configuration, ils seraient apparus en Europe du Nord, à une époque où le pôle se situait au Sud du Groenland, soit pendant l'ère glacière où le niveau de la mer était inférieur de 200 m, ce qui laisse supposer que l'étendue océanique actuelle, recouvrant l'espace sis entre la Galice et l'Irlande, aurait été une zone de toundras, idéale pour l'élevage du renne. La montée des eaux, due au réchauffement du climat et au basculement du pôle vers sa position actuelle, aurait provoqué un reflux des chasseurs-éleveurs de rennes vers le sud de la Gaule et les Asturies d'abord, vers le reste de l'Europe, en particulier la Scandinavie à peine libérée des glaces, ensuite. Une autre branche aurait rejoint les plaines d'Amérique du Nord, pour y rencontrer une population asiatique et créer, par mixage avec elle, une race nouvelle. De cette hypothèse sur l'origine des populations europides et amérindiennes, Wirth déduit la théorie d'un diffusionnisme racial/racisant, accompagné d'une thèse audacieuse sur le matriarchat originel, prenant le relais de celle de Bachofen.

Wirth croyait qu'un manuscrit frison du Moyen-Age, l'Oera-Linda bok, recopié à chaque génération depuis environ le Xième siècle jusqu'au XVIIIième, contenait in nuce le récit de l'inondation des toundras atlantiques et de la zone du Dogger Bank. Cette affirmation de Wirth n'a guère été prise au sérieux et l'a mis au ban de la communauté scientifique. Toutefois, le débat sur l'Oera-Linda bok n'est pas encore clos aux Pays-Bas aujourd'hui.

Très en vogue parmi les ethnologues, les folkloristes et les "symbolologues" en Allemagne, en Flandre, aux Pays-Bas et en Scandinavie avant-guerre, Wirth a été oublié, en même temps que les théoriciens allemands et néerlandais de la race, compromis avec le IIIième Reich. Or Wirth ne peut être classé dans la même catégorie qu'eux: d'abord parce qu'il estimait que la recherche des racines de la germanité, objectif positif, était primordiale, et que l'antisémitisme, attitude négative, était "une perte de temps"; ensuite, en butte à l'hostilité de Rosenberg, il est interdit de publication. Il reçoit temporairement l'appui de Himmler mais rompt avec lui en 1938, jugeant que les prétoriens du IIIième Reich, les SS, sont une incarnation moderne des Männerbünde (des associations masculines) qui ont éradiqué, par le truchement du wotanisme puis du christianisme, les cultes des mères, propres à la culture matricielle atlanto-arctique et à son matriarchat apaisant, remontant à la fin du pliocène. Arrêté par les Américains en 1945, il est rapidement relaché, les enquêteurs ayant conclu qu'il avait été un "naïf abusé". Infatigable, il poursuit après guerre ses travaux, notamment dans le site mégalithique des Externsteine dans le centre de l'Allemagne et organise pendant deux ans, de 1974 à 1976, une exposition sur les communautés préhistoriques d'Europe. Il meurt à Kusel dans le Palatinat le 16 février 1981. Sans corroborer toutes les thèses de Wirth, les recherches des Britanniques Renfrew et Hawkins et du Français Jean Deruelle ont permis de revaloriser les civilisations mégalithiques ouest-européennes et de démontrer, notamment grâce au carbone 14, leur antériorité par rapport aux civilisations égyptienne, crétoise et mésopotamienne.

L'ascension de l'humanité (Der Aufgang der Menschheit), 1928

Ouvrage majeur de Wirth, Der Aufgang der Menschheit se déploie à partir d'une volonté de reconnaître le divin dans le monde et de dépasser l'autorité de type augustinien, reposant sur la révélation d'un Dieu extérieur aux hommes. Wirth entend poursuivre le travail amorcé par la Réforme, pour qui l'homme a le droit de connaître les vérités éternelles car Dieu l'a voulu ainsi. Wirth procède à une typologie racisée/localisée des religiosités: celles qui acceptent la révélation sont méridionales et orientales; celles qui favorisent le déploiement à l'infini de la connaissance sont "nordiques". La tâche à parfaire, selon Wirth, c'est de dépasser l'irreligion contemporaine, produit de la mécanisation et de l'économisme, en se plongeant dans l'exploration de notre passé. Seule une connaissance du passé le plus lointain permet de susciter une vie intérieure fondée, de renouer avec une religiosité spécifique, sans abandonner la démarche scientifique de recherche et sans sombrer dans les religiosités superficielles de substitution (pour Wirth: le néo-catholicisme, la théosophie ou l'anthroposophie de Steiner). Les travaux archéologiques ont permis aux Européens de replonger dans leur passé et de reculer très loin dans le temps les débuts hypothétiques de l'histoire. Parmi les découvertes de l'archéologie: les signes symboliques abstraits des sites "préhistoriques" de Gourdan, La Madeleine, Rochebertier et Traz-os-Montes (Portugal), dans le Sud-Ouest européen atlantique. Pour la science universitaire officielle, l'alphabet phénicien était considéré comme le premier système d'écriture alphabétique d'où découlaient tous les autres. Les signes des sites atlantiques ibériques et aquitains n'étaient, dans l'optique des archéologues classiques, que des "griffonnages ludiques". L'¦uvre de Wirth s'insurge contre cette position qui refuse de reconnaître le caractère d'abord symbolique du signe qui ne deviendra phonétique que bien ultérieurement. L'origine de l'écriture remonte donc au Magdalénien: l'alphabet servait alors de calendrier et indiquait, à l'aide de symboles graphiques abstraits, la position des astres. Vu la présence de cette écriture linéaire, indice de civilisation, la distinction entre "histoire" et "préhistoire" n'a plus aucun sens: notre chronologie doit être reculée de 10.000 années au moins, conclut Wirth. L'écriture linéaire des populations du Magdalénien atlantique d'Ibérie, d'Aquitaine et de l'Atlas constituerait de ce fait l'écriture primordiale et les systèmes égyptiens et sumériens en seraient des dégénérescences imagées, moins abstraites. Théorie qui inverse toutes les interprétations conventionnelles de l'histoire et de la "pré-histoire" (terme que conteste Wirth). Der Aufgang der Menschheit commence par une "histoire de l'origine des races humaines" (Zur Urgeschichte der Rassen). Celle-ci débute à la fin de l'ère tertiaire, quand le rameau humain se sépare des autres rameaux des primates et qu'apparaissent les différents groupes sanguins (pour Wirth, le groupe I, de la race originelle ‹Urrasse‹ arctique-nordique, précédant la race nordique proprement dite, et le groupe III de la race originelle sud-asiatique). Ce processus de différenciation raciale s'opère pendant l'éocène, l'oligocène, le miocène et le pliocène. A la fin de ces ères tertiaires, s'opère un basculement du pôle arctique qui inaugure une ère glaciaire en Amérique du Nord (glaciation de Kansan). Au début du quaternaire, cette glaciation se poursuit (en Amérique: glaciations de Günz, de l'Illinois et de l'Iowa; en Europe, glaciation de Mindel). Ces glaciations sont contemporaines des premiers balbutiements du paléolithique (culture des éolithes) et, pour Wirth, des premières migrations de la race originelle arctique-nordique vers l'Amérique du Nord, l'Atlantique Nord et l'Asie septentrionale, ce qui donne en Europe les cultures "pré-historiques" du Strépyen et du Pré-Chelléen. Le réchauffement du climat, à l'ère chelléenne, permet aux éléphants, rhinocéros et hippopotames de vivre en Europe. L'Acheuléen inaugure un rafraîchissement du climat, qui fait disparaître cette faune; ensuite, à l'ère moustérienne, s'enclenche une nouvelle glaciation (dite de Riß ou de Würm; en Amérique, première glaciation du Wisconsin). Sur le plan racial, l'Europe est peuplée par la race de Néanderthal et les hommes du Moustier, de Spy, de la Chapelle-aux-Saints, de La Ferrasie, de La Quina et de Krapina. Lors d'un léger réchauffement du climat, apparaît la race d'Aurignac, influencée par des éléments de la race arctique-nordique-atlantique, porteuse des premiers signes graphiques symboliques. C'est l'époque des cultures préhistoriques de l'Europe du Sud-Ouest, de la zone franco-cantabrique (squelette de Cro-Magnon, type humain mélangé, où se croise le sang arctique nordique et celui des populations non nordiques de l'Europe), à l'ère dite du Magdalénien (I & II). Epoque-charnière dans l'optique de Wirth, puisqu'apparaissent, sur les parois des cavernes, notamment celles de La Madeleine, de Gourdan et du Font de Gaume en France, d'Altamira en Espagne, les dessins rupestres et les premières signes symboliques. Vers 12.000 avant notre ère, le climat se réchauffe et le processus de mixage entre populations arctiques-atlantiques-nordiques et Pré-Finnois de l'aire baltique (culture de Maglemose au Danemark) ou éléments alpinoïdes continentaux se poursuit, formant les différentes sous-races européennes. La Mer du Nord n'existe pas encore et l'espace du Dogger Bank (pour Wirth, le Polsete-Land) est occupé par le peuple Tuatha, de souche arctique-nordique, qui conquiert, à l'Est, le Nord-Ouest de l'Europe et, à l'Ouest, l'Irlande, qu'il arrache aux tribus "sud-atlantiques", les Fomoriens. La Mer du Nord disparaît sous les flots et, selon la thèse très contestée de Wirth, les populations arctiques-nordiques émigrent par vagues successives pendant plusieurs millénaires dans toute l'Europe, le bassin méditerranéen et le Moyen-Orient, transmettant et amplifiant leur culture originelle, celle des mégalithes. En Europe orientale, elles fondent les cultures dites de Tripolje, Vinça et Tordos, détruisent les palais crétois vers 1400 avant notre ère, importent l'écriture linéaire dans l'espace sumérien et élamite, atteignent les frontières occidentales de la Chine, s'installent en Palestine (les Amourou du Pays de Canaan vers -3000 puis les Polasata et les Thakara vers -1300/-1200), donnent naissance à la culture phénicienne qui rationalise et fonctionnalise leurs signes symboliques en un alphabet utilitaire, introduisent les dolmens en Afrique du Nord et la première écriture linéaire pré-dynastique en Egypte (-3300), etc.

Pour prouver l'existence d'une patrie originelle arctique, Wirth a recours aux théories de la dérive des continents de W. Köppen et A. Wegener (Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane, 1922) et aux résultats de l'exploration des fonds maritimes arctiques et des restes de flore qu'O. Heer y a découverts (Flora fossilis artica, Zürich, 1868-1883). A la fin du tertiaire et aux débuts du quaternaire, les continents européen et américain étaient encore soudés l'un à l'autre. La dérive de l'Amérique vers l'ouest et vers le sud aurait commencé lors de la grande glaciation du pléistocène. Le Groenland, les Iles Spitzbergen, l'Islande et la Terre de Grinell, avec le plateau continental qui les entoure, seraient donc la terre originelle de la race arctique-nordique, selon Wirth. Le plateau continental, aujourd'hui submergé, s'étendant de l'Ecosse et l'Irlande aux côtes galiciennes et asturiennes serait, toujours selon Wirth, la seconde patrie d'origine de ces populations. Comme preuve supplémentaire de l'origine "circum-polaire" des populations arctiques-nordiques ultérieurement émigrées jusqu'aux confins de la Chine et aux Indes, Wirth cite l'Avesta, texte sacré de l'Iran ancien, qui parle de dix mois d'hiver et de deux mois d'été, d'un hiver si rigoureux qu'il ne permettait plus aux hommes et au bétail de survivre, d'inondations post-hivernales, etc. La tradition indienne, explorée par Bal Gangâdhar Tilak (The Arctic Home in the Vedas, 1903), parle, elle, d'une année qui compte un seul jour et une seule nuit, ce qui est le cas au niveau du pôle. Aucun squelette de type arctique-nordique n'a été retrouvé, ni en Ecosse ou en Irlande, zones arctiques non inondées, ni le long des routes des premières migrations (Dordogne/Aquitaine, Espagne, Atlas, etc. jusqu'en Indonésie), parce que les morts étaient d'abord enfouis six mois dans le giron de la Terre-mère pour être ensuite exhumés et exposés sur une dalle plate, un pré-dolmen, pour être offerts à la lumière, pour renaître et retourner à la lumière, comme l'atteste le Vendidad iranien, la tradition des Parses et les coutumes funéraires des Indiens d'Amérique du Nord.

L'organisation sociale des premiers groupes de migrants arctiques-nordiques est purement matriarcale: les femmes y détiennent les rôles dominants et sont dépositaires de la sagesse.

En posant cette série d'affirmations, difficiles à étayer par l'archéologie, Wirth lance un défi aux théories des indo-européanisants qui affirment l'origine européenne/continentale des "Indo-Européens" nordiques (appelation que Wirth conteste parce qu'il juge qu'elle jette la confusion). La race nordique et, partant, les "Indo-Européens" ne trouvent pas, pour Wirth, leur origine sur le continent européen ou asiatique. Il n'y aurait jamais eu, selon lui, d'Urvolk indo-européen en Europe car les nordiques apparaissent toujours mélangés sur cette terre; les populations originelles de l'Europe sont finno-asiatiques. Les Nordiques ont pénétré en Europe par l'Ouest, en longeant les voies fluviales, en quittant leurs terres progressivement inondées par la fonte des glaces arctiques. Cette migration a rencontré la vague des Cro-Magnons sud-atlantiques (légèrement métissés d'arcto-nordiques depuis l'époque des Aurignaciens) progressant vers l'Est. La culture centre-européenne du néolithique est donc le produit d'un vaste métissage de Sud-Atlantiques, de Nordiques et de Finno-asiatiques, que prouvent les études sérologiques et la présence des symboles. Les Celtes procèdent de ce mélange et ont constitué une civilisation qui a progressé en inversant les routes migratoires et en revenant en Irlande et dans la zone franco-cantabrique, emmenant dans leur sillage des éléments raciaux finno-asiatiques. En longeant le Rhin, ils ont traversé la Mer du Nord et soumis en Irlande le peuple nordique des Tuatha, venu de la zone inondée du Dogger Bank (Polsete-Land) et évoqué dans les traditions mythologiques celto-irlandaises. L'irruption des Celtes met fin à la culture matriarcale et monothéiste des Tuatha de l'ère mégalithique pour la remplacer par le patriarcat polythéiste d'origine asiatique, organisé par une caste de chamans, les druides. Wirth se réfère à Ammien Marcellin (1. XV, c.9, §4) pour étayer sa thèse: celui-ci parle des trois races de l'Irlande: l'autochtone, celle venue des "îles lointaines" et celle venue du Rhin, soit la sud-atlantique fomorienne, les Tuatha arcto-nordiques et les Celtes.

Le symbolisme graphique abstrait, que nous ont laissé ces peuples arcto-nordiques, temoigne d'une religiosité cosmique, d'un regard jeté sur le divin cosmique, d'une religiosité basée sur l'expérience du "mystère sacré" de la lumière boréale, de la renaissance solaire au solstice d'hiver. Dans cette religiosité, les hommes sont imbriqués entièrement dans la grande loi qui préside aux mutations cosmiques, marquée par l'éternel retour. La mort est alors un re-devenir (ein Wieder-Werden). Le divin est père, Weltgeist, depuis toujours présent et duquel procèdent toutes choses. Il envoie son fils, porteur de la "lumière des terres", pour se révéler aux hommes. Les hiéroglyphes qui expriment la présence de ce dieu impersonnel, qui se révèle par le soleil, se réfèrent au cycle annuel, aux rotations de l'univers, aux mutations incessantes qui l'animent, au cosmos, au ciel et à la terre. L'étymologie de tu-ath (vieil-irl.), ou de ses équivalents lituanien (ta-uta), osque (to-uto), vieux-saxon (thi-od), dérive des racines *ti, *to, *tu (dieu) et *ot, *ut, *at (vie, souffle, âme).

Ce peuple, connaisseur du "souffle divin", soit du mouvement des astres, a élaboré un système de signes correspondant à la position des planètes et des étoiles. Les modifications de ces systèmes de signes astronomiques étaient entraînées par les mouvements des corps célestes. Toute la civilisation mégalithique, explique Wirth, avant Renfrew, Hawkins et Deruelle, procède d'une religiosité astronomique. Elle est née en Europe occidentale et septentrionale et a essaimé dans le monde entier: en Amérique du Nord, au Maghreb (les mégalithes de l'Atlas), en Egypte, en Mésopotamie et, vraisemblablement, jusqu'en Indonésie et peut-être en Nouvelle-Zélande (les Maoris).

(Robert Steuckers).

- Bibliographie: Pour une bibliographie très complète, se référer au travail d'Eberhard Baumann, Verzeichnis der Schriften von Herman Felix WIRTH Roeper Bosch von 1911 bis 1980 sowie die Schriften für, gegen, zu und über die Person und das Werk von Herman Wirth, Gesellschaft für Europäische Urgemeinschaftskunde e.V., Kolbenmoor, 1988. Notre liste ci-dessous ne reprend que les ouvrages principaux: Der Untergang des niederländischen Volksliedes, La Haye, 1911; Um die wissenschaftliche Erkenntnis und den nordischen Gedanken, Berlin, 1929 (?); Der Aufgang der Menschheit, Iéna, 1928 (2ième éd., 1934); Die Heilige Urschrift der Menschheit, Leipzig, 1931-36; Was heißt deutsch? Ein urgeistgeschichtlicher Rückblick zur Selbstbestimmung und Selbstbesinnung, Iéna, 1931 (2ième éd., 1934); Führer durch die Erste urreligionsgeschichtliche Ausstellung "Der Heilbringer". Von Thule bis Galiläa und von Galiläa bis Thule, Berlin/Leipzig, 1933; Die Ura-Linda-Chronik, Leipzig, 1933; Die Ura-Linda-Chronik. Textausgabe (texte de la Chronique d'Oera-Linda traduit par H.W.), Leipzig, 1933; Um den Ursinn des Menschseins, Vienne, 1960; Der neue Externsteine-Führer, Marbourg, 1969; Allmutter. Die Entdeckung der "altitalischen" Inschriften in der Pfalz und ihre Deutung, Marbourg, 1974; Führer durch das Ur-Europa-Museum mit Einführung in die Ursymbolik und Urreligion, Marbourg, 1975; Europäische Urreligion und die Externsteine, Vienne, 1980.

- Sur Wirth: consulter la bibliographie complète de Eberhard Baumann (op. cit.); cf. également: Eberhard Baumann, Der Aufgang und Untergang der frühen Hochkulturen in Nord- und Mitteleuropa als Ausdruck umfassender oder geringer Selbstverwirklung (oder Bewußtseinsentfaltung) dargestellt am Beispiel des Erforschers der Symbolgeschichte Professor Dr. Herman Felix Wirth, Herborn-Schönbach, 1990 (disponible chez l'auteur: Dr. E. Baumann, Linzer Str. 12, D-8390 Passau). Cf. également: Walter Drees, Herman Wirth bewies: die arktisch-atlantische Kulturgrundlage schuf die Frau, Vlotho-Valdorf, chez l'auteur (Kleeweg 6, D-4973 Vlotho-Valdorf); Dr. A. Lambardt, Ursymbole der Megalithkultur. Zeugnisse der Geistesurgeschichte, Heitz u. Höffkes, Essen, s.d.

Othmar Spann: A Catholic Radical Traditionalist

By Lucian Tudor

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Othmar

Spann was an Austrian philosopher who was a key influence on German

conservative and traditionalist thought in the period after World War I,

and he is thus considered a representative of the intellectual movement

known as the “Conservative Revolution.” Spann was a professor of

economics and sociology at the University of Vienna, where he taught not

only scientific social and economic theories, but also influenced many

students with the presentation of his worldview in his lectures. As a

result of this he formed a large group of followers known as the Spannkreis

(“Spann Circle”). This circle of intellectuals attempted to influence

politicians who would be sympathetic to “Spannian” philosophy in order

to actualize its goals.[1]

Othmar

Spann was an Austrian philosopher who was a key influence on German

conservative and traditionalist thought in the period after World War I,

and he is thus considered a representative of the intellectual movement

known as the “Conservative Revolution.” Spann was a professor of

economics and sociology at the University of Vienna, where he taught not

only scientific social and economic theories, but also influenced many

students with the presentation of his worldview in his lectures. As a

result of this he formed a large group of followers known as the Spannkreis

(“Spann Circle”). This circle of intellectuals attempted to influence

politicians who would be sympathetic to “Spannian” philosophy in order

to actualize its goals.[1]Othmar Spann himself was influenced by a variety of philosophers across history, including Plato, Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, J. G. Fichte, Franz von Baader, and most notably the German Romantic thought of Adam Müller. Spann called his own worldview “Universalism,” a term which should not be confused with “universalism” in the vernacular sense; for the former is nationalistic and values particularity while the latter refers to cosmopolitan or non-particularist (even anti-particularist) ideas. Spann’s term is derived from the root word “universality,” which is in this case synonymous with related terms such as collectivity, totality, or whole.[2] Spann’s Universalism was expounded in a number of books, most notably in Der wahre Staat (“The True State”), and essentially taught the value of nationality, of the social whole over the individual, of religious (specifically Catholic) values over materialistic values, and advocated the model of a non-democratic, hierarchical, and corporatist state as the only truly valid political constitution.

Social Theory

Othmar Spann declared: “It is the fundamental truth of all social science . . . that not individuals are the truly real, but the whole, and that the individuals have reality and existence only so far as they are members of the whole.”[3] This concept, which is at the core of Spann’s sociology, is not a denial of the existence of the individual person, but a complete denial of individualism; individualism being that ideology which denies the existence and importance of supra-individual realities. Classical liberal theory, which was individualist, held an “atomistic” view of individuals and regarded only individuals as truly real; individuals which it believed were essentially disconnected and independent from each other. It also held that society only exists as an instrumental association as a result of a “social contract.” On the other hand, sociological studies have disproven this theory, showing that the whole (society) is never merely the sum of its parts (individuals) and that individuals naturally have psychological bonds with each other. This was Othmar Spann’s position, but he had his own unique way of formulating it.[4]

While the theory of individualism appears, superficially, to be correct to many people, an investigation into the matter shows that it is entirely fallacious. Individuals never act entirely independently because their behavior is always at least in part determined by the society in which they live, and by their organic, non-instrumental (and thus also non-contractual) bonds with other people in their society. Spann wrote, “according to this view, the individual is no longer self-determined and self-created, and is no longer based exclusively and entirely on its own egoicity.”[5] Spann conceived of the social order, of the whole, as an organic society (a community) in which all individuals belonging to it have a pre-existing spiritual unity. The individual person emerges as such from the social whole to which he was born and from which he is never really separated, and “thus the individual is that which is derivative.”[6]

Therefore, society is not merely a mechanical aggregate of fundamentally disparate individuals, but a whole, a community, which precedes its parts, the individuals. “Universalists contend that the mental or spiritual associative tie between individuals exists as an independent entity . . .”[7] However, Spann clarified that this does not mean that the individual has “no mental self-sufficiency,” but rather that he actualizes his personal being only as a member of the whole: “he is only able to form himself, is only able to build up his personality, when in close touch with others like unto himself; he can only sustain himself as a being endowed with mentality or spirituality, when he enjoys intimate and multiform communion with other beings similarly endowed.”[8] Therefore,

All

spiritual reality present in the individual is only there and only

comes into being as something that has been awakened . . . the

spirituality that comes into being in an individual (whether directly or

mediated) is always in some sense a reverberation of that which another

spirit has called out to the individual. This means that human

spirituality exists only in community, never in spiritual isolation. . .

. We can say that individual spirituality only exists in community or

better, in ‘spiritual community’ [Gezweiung]. All spiritual essence and reality exists as ‘spiritual community’ and only in ‘communal spirituality’ [Gezweitheit].[9]

It

is also important to clarify that Spann’s concept of society did not

conceive of society as having no other spiritual bodies within it that

were separate from each other. On the contrary, he recognized the

importance of the various sub-groups, referred to by him as “partial

wholes,” as constituent parts and elements which are different yet

related, and which are harmonized by the whole under which they exist.

Therefore, the whole or the totality can be understood as the unity of

individuals and “partial wholes.” To reference a symbolic image,

“Totality [the Whole] is analogous to white light before it is refracted

by a prism into many colors,” in which the white light is the

supra-temporal totality, while the prism is cosmic time which “refracts

the totality into the differentiated and individuated temporal

reality.”[10]Nationality and Racial Style

Volk (“people” or “nation”), which signifies “nationality” in the cultural and ethnic sense, is an entirely different entity and subject matter from society or the whole, but for Spann the two had an important connection. Spann was a nationalist and, defining Volk in terms of belonging to a “spiritual community” with a shared culture, believed that a social whole is under normal conditions only made up of a single ethnic type. Only when people shared the same cultural background could the deep bonds which were present in earlier societies truly exist. He thus upheld the “concept of the concrete cultural community, the idea of the nation – as contrasted with the idea of unrestricted, cosmopolitan, intercourse between individuals.”[11]

Spann advocated the separation of ethnic groups under different states and was also a supporter of pan-Germanism because he believed that the German people should unite under a single Reich. Because he also believed that the German nation was intellectually superior to all other nations (a notion which can be considered as the unfortunate result of a personal bias), Spann also believed that Germans had a duty to lead Europe out of the crisis of liberal modernity and to a healthier order similar to that which had existed in the Middle Ages.[12]

Concerning the issue of race, Spann attempted to formulate a view of race which was in accordance with the Christian conception of the human being, which took into account not only his biology but also his psychological and spiritual being. This is why Spann rejected the common conception of race as a biological entity, for he did not believe that racial types were derived from biological inheritance, just as he did not believe an individual person’s character was set into place by heredity. Rather what race truly was for Spann was a cultural and spiritual character or type, so a person’s “racial purity” is determined not by biological purity but by how much his character and style of behavior conforms to a specific spiritual quality. In his comparison of the race theories of Spann and Ludwig Ferdinand Clauss (an influential race psychologist), Eric Voegelin had concluded:

In

Spann’s race theory and in the studies of Clauss we find race as the

idea of a total being: for these two scholars racial purity or blood

purity is not a property of the genetic material in the biological

sense, but rather the stylistic purity of the human form in all its

parts, the possession of a mental stamp recognizably the same in its

physical and psychological expression.[13]

However,

it should be noted that while Ludwig Clauss (like Spann) did not

believe that spiritual character was merely a product of genetics, he

did in fact emphasize that physical race had importance because the

bodily racial form must be essentially in accord with the psychical

racial form with which it is associated, and with which it is always

linked. As Clauss wrote,

The

style of the psyche expresses itself in its arena, the animate body.

But in order for this to be possible, this arena itself must be governed

by a style, which in turn must stand in a structured relationship to

the style of the psyche: all the features of the somatic structure are,

as it were, pathways for the expression of the psyche. The racially

constituted (that is, stylistically determined) psyche thus acquires a

racially constituted animate body in order to express the racially

constituted style of its experience in a consummate and pure manner. The

psyche’s expressive style is inhibited if the style of its body does

not conform perfectly with it.[14]

Likewise

Julius Evola, whose thought was influenced by both Spann and Clauss,

and who expanded Clauss’s race psychology to include religious matters,

also affirmed that the body had a certain level of importance.[15]On the other hand, the negative aspect of Othmar Spann’s theory of race is that it ends up dismissing the role of physical racial type entirely, and indeed many of Spann’s major works do not even mention the issue of race. A consequence of this was also the fact that Spann tolerated and even approved of critiques made by his students of National Socialist theories of race which emphasized the role of biology; an issue which would later compromise his relationship with that movement even though he was one of its supporters.[16]

The True State

Othmar Spann’s Universalism was in essence a Catholic form of “Radical Traditionalism”; he believed that there existed eternal principles upon which every social, economic, and political order should be constructed. Whereas the principles of the French Revolution – of liberalism, democracy, and socialism – were contingent upon historical circumstances, bound by world history, there are certain principles upon which most ancient and medieval states were founded which are eternally valid, derived from the Divine order. While specific past state forms which were based on these principles cannot be revived exactly as they were because they held many characteristics which are outdated and historical, the principles upon which they were built and therefore the general model which they provide are timeless and must reinstituted in the modern world, for the systems derived from the French Revolution are invalid and harmful.[17] This timeless model was the Wahre Staat or “True State” – a corporative, monarchical, and elitist state – which was central to Universalist philosophy.

1. Economics

In terms of economics, Spann, like Adam Müller, rejected both capitalism and socialism, advocating a corporatist system relatable to that of the guild system and the landed estates of the Middle Ages; a system in which fields of work and production would be organized into corporations and would be subordinated in service to the state and to the nation, and economic activity would therefore be directed by administrators rather than left solely to itself. The value of each good or commodity produced in this system was determined not by the amount of labor put into it (the labor theory of value of Marx and Smith), but by its “organic use” or “social utility,” which means its usefulness to the social whole and to the state.[18]

Spann’s major reason for rejecting capitalism was because it was individualistic, and thus had a tendency to create disharmony and weaken the spiritual bonds between individuals in the social whole. Although Spann did not believe in eliminating competition from economic life, he pointed out that the extreme competition glorified by capitalists created a market system in which there occurred a “battle of all against all” and in which undertakings were not done in service to the whole and the state but in service to self-centered interests. Universalist economics aimed to create harmony in society and economics, and therefore valued “the vitalising energy of the personal interdependence of all the members of the community . . .”[19]

Furthermore, Spann recognized that capitalism also did result in an unfair treatment by capitalists of those underneath them. Thus while he believed Marx’s theories to be theoretically flawed, Spann also mentioned that “Marx nevertheless did good service by drawing attention to the inequality of the treatment meted out to worker and to entrepreneur respectively in the individualist order of society.”[20] Spann, however, rejected socialist systems in general because while socialism seemed superficially Universalistic, it was in fact a mixture of Universalist and individualist elements. It did not recognize the primacy of the State over individuals and also held that all individuals in society should hold the same position, eliminating all class distinctions, and should receive the same amount of goods. “True universalism looks for an organic multiplicity, for inequality,” and thus recognizes differences even if it works to establish harmony between the parts.[21]

2. Politics

Spann asserted that all democratic political systems were an inversion of the truly valuable political order, which was of even greater importance than the economic system. A major problem of democracy was that it allowed, firstly, the manipulation of the government by wealthy capitalists and financiers whose moral character was usually questionable and whose goals were almost never in accord with the good of the community; and secondly, democracy allowed the triumph of self-interested demagogues who could manipulate the masses. However, even the theoretical base of democracy was flawed, according to Spann, because human beings were essentially unequal, for individuals are always in reality differentiated in their qualities and thus are suited for different positions in the social order. Democracy thus, by allowing a mass of people to decide governmental matters, meant excluding the right of superior individuals to determine the destiny of the State, for “setting the majority in the saddle means that the lower rule over the higher.”[22]

Finally, Spann noted that “demands for democracy and liberty are, once more, wholly individualistic.”[23] In the Universalist True State, the individual would subordinate his will to the whole and would be guided by a sense of selfless duty in service to the State, as opposed to asserting his individual will against all other wills. Furthermore, the individual did not possess rights because of his “rational” character and simply because of being human, as many Enlightenment thinkers asserted, but these rights were derived from the ethics of the particular social whole to which he belonged and from the laws of the State.[24] Universalism also acknowledged the inherent inequalities in human beings and supported a hierarchical organization of the political order, where there would be only “equality among equals” and the “subordination of the intellectually inferior under their intellectual betters.”[25]

In the True State, individuals who demonstrated their leadership skills, their superior nature, and the right ethical character would rise among the levels of the hierarchy. The state would be led by a powerful elite whose members would be selected from the upper levels of the hierarchy based on their merit; it was essentially a meritocratic aristocracy. Those in inferior positions would be taught to accept their role in society and respect their superiors, although all parts of the system are “nevertheless indispensable for its survival and development.”[26] Therefore, “the source of the governing power is not the sovereignty of the people, but the sovereignty of the content.”[27]

Othmar Spann, in accordance with his Catholic religious background, believed in the existence of a supra-sensual, metaphysical, and spiritual reality which existed separately from and above the material reality, and of which the material realm was its imperfect reflection. He asserted that the True State must be animated by Christian spirituality, and that its leaders must be guided by their devotion to Divine laws; the True State was thus essentially theocratic. However, the leadership of the state would receive its legitimacy not only from its religious character, but also by possessing “valid spiritual content,” which “precedes power as it is represented in law and the state.”[28] Thus Spann concluded that “history teaches us that it is the validity of spiritual values that constitutes the spiritual bond. They cannot be replaced by fire and sword, nor by any other form of force. All governance that endures, and all the order that society has thus achieved, is the result of inner domination.”[29]

The state which Spann aimed to restore was also federalistic in nature, uniting all “partial wholes” – corporate bodies and local regions which would have a certain level of local self-governance – with respect to the higher Authority. As Julius Evola wrote, in a description that is in accord with Spann’s views, “the true state exists as an organic whole comprised of distinct elements, and, embracing partial unities [wholes], each possesses a hierarchically ordered life of its own.”[30] All throughout world history the hierarchical, corporative True State appears and reappears; in the ancient states of Sparta, Rome, Persia, Medieval Europe, and so on. The structures of the states of these times “had given the members of these societies a profound feeling of security. These great civilizations had been characterized by their harmony and stability.”[31]

Liberal modernity had created a crisis in which the harmony of older societies was damaged by capitalism and in which social bonds were weakened (even if not eliminated) by individualism. However, Spann asserted that all forms of liberalism and individualism are a sickness which could never succeed in fully eliminating the original, primal reality. He predicted that in the era after World War I, the German people would reassert its rights and would create revolution restoring the True State, would recreate that “community tying man to the eternal and absolute forces present in the universe,”[32] and whose revolution would subsequently resonate all across Europe, resurrecting in modern political life the immortal principles of Universalism.

Spann’s Influence and Reception

Othmar Spann and his circle held influence largely in Germany and Austria, and it was in the latter country that their influence was the greatest. Spann’s philosophy became the basis of the ideology of the Austrian Heimwehr (“Home Guard”) which was led by Ernst Rüdiger von Starhemberg. Leaders of the so-called “Austro-fascist state,” including Engelbert Dollfuss and Kurt Schuschnigg, were also partially influenced by Spann’s thought and by members of the “Spann circle.”[33] However, despite the fact that this state was the only one which truly attempted to actualize his ideas, Spann did not support “Austro-fascism” because he was a pan-Germanist and wanted the German people unified under a single state, which is why he joined Hitler’s National Socialist movement, which he believed would pave the way to the True State.

Despite repeated attempts to influence National Socialist ideology and the leaders of the NSDAP, Spann and his circle were rejected by most National Socialists. Alfred Rosenberg, Robert Ley, and various other authors associated with the SS made a number of attacks on Spann’s school. Rosenberg was annoyed both by Spann’s denial of the importance of blood and by his Catholic theocratic position; he wrote that “the Universalist school of Othmar Spann has successfully refuted idiotic materialist individualism . . . [but] Spann asserted against traditional Greek wisdom, and claimed that god is the measure of all things and that true religion is found only in the Catholic Church.”[34]

Aside from insisting on the reality of biological laws, other National Socialists also criticized Spann’s political proposals. They asserted that his hierarchical state would create a destructive divide between the people and their elite because it insisted on their absolute separateness; it would destroy the unity they had established between the leadership and the common folk. Although National Socialism itself had elements of elitism it was also populist, and thus they further argued that every German had the potential to take on a leadership role, and that therefore, if improved within in the Volksgemeinschaft (“Folk-Community”), the German people were thus not necessarily divisible in the strict view of superior elites and inferior masses.[35]

As was to be expected, Spann’s liberal critics complained that his anti-individualist position was supposedly too extreme, and the social democrats and Marxists argued that his corporatist state would take away the rights of the workers and grant rulership to the bourgeois leaders. Both accused Spann of being an unrealistic reactionary who wanted to revive the Middle Ages.[36] However, here we should note here that Edgar Julius Jung, who was himself basically a type of Universalist and was heavily inspired by Spann’s work, had mentioned that:

We

are reproached for proceeding alongside or behind active political

forces, for being romantics who fail to see reality and who indulge in

dreams of an ideology of the Reich that turns toward the past. But form

and formlessness represent eternal social principles, like the struggle

between the microcosm and the macrocosm endures in the eternal swing of

the pendulum. The phenomenal forms that mature in time are always new,

but the great principles of order (mechanical or organic) always remain

the same. Therefore if we look to the Middle Ages for guidance, finding

there the great form, we are not only not mistaking the present time but

apprehending it more concretely as an age that is itself incapable of

seeing behind the scenes.[37]

Edgar

Jung, who was one of Hitler’s most prominent radical Conservative

opponents, expounded a philosophy which was remarkably similar to

Spann’s, although there are some differences we would like to point out.

Jung believed that neither Fascism nor National Socialism were

precursors to the reestablishment of the True State but rather “simply

another manifestation of the liberal, individualistic, and secular

tradition that had emerged from the French Revolution.”[38] Fascism and

National Socialism were not guided by a reference to a Divine power and

were still infected with individualism, which he believed showed itself

in the fact that their leaders were guided by their own ambitions and

not a duty to God or a power higher than themselves.Edgar Jung also rejected nationalism in the strict sense, although he simultaneously upheld the value of Volk and the love of fatherland, and advocated the reorganization of the European continent on a federalist basis with Germany being the leading nation of the federation. Also in contrast to Spann’s views, Jung believed that genetic inheritance did play a role in the character of human beings, although he believed this role was secondary to cultural and spiritual factors and criticized common scientific racialism for its “biological materialism.”

Jung asserted that what he saw as superior racial elements in a population should be strengthened and the inferior elements decreased: “Measures for the raising of racially valuable components of the German people and for the prevention of inferior currents must however be found today rather than tomorrow.”[39] Jung also believed that the elites of the Reich, while they should be open to accepting members of lower levels of the hierarchy who showed leadership qualities, should marry only within the elite class, for in this way a new nobility possessing leadership qualities strengthened both genetically and spiritually would be developed.[40]