“I do not appeal to the professional classes, who, in Ireland, at least, appear at no time to

have thought of the affairs of their country till they first feared for

their emoluments – nor do I appeal to the shoddy society of ‘West Britonism‘ – but to those young men clustered here and there throughout our land, whom the emotion of patriotism has lifted into that world of selfless passion in which heroic deeds are possible and heroic poetry credible.” – Ireland and the Arts. W.B. Yeats.

The political and cultural figures present in the early foundation of the Irish State present Irish liberals with some quandaries. Beneath the narrative of Irish independence being an inherently progressive movement betrayed by a post-Treaty “carnival of reaction”, lies an irreconcilable fact that the many of the figures driving separation from Britain belonged to a stridently conservative brand of thinking. Any budding conservative movement in Ireland should embrace these figures and cultivate a counter-narrative in response to the simplistic mistruths presented in works such as Ken Loach’s “Wind that Shakes the Barley”. Here, the Irish struggle is distilled down to a failed left wing revolt and those of a conservative inclination are portrayed as flagrantly unpatriotic and sometimes even at odds with Irish language revivalism.

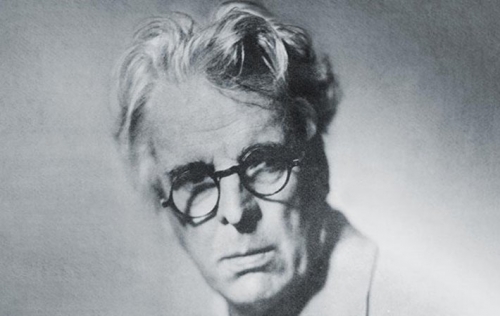

The character of W.B. Yeats ranks perhaps first and foremost amongst those figures. Despite his Anglo-Irish background, he threw himself wholeheartedly behind not merely the political separation of his country from Britain, but the equally important task of forming a distinct Irish consciousness. First a political Tory committed to the cause of Irish freedom, he later became a reform-minded senator campaigning against the myopia of the Church-dominated Free State whilst simultaneously advocating for a more conservative state. Yeats, from the onset, strikes the modern reader as an enigma with his distinct brand of politics.

Yeats formed a central plank in what is now termed the Gaelic Revival, a cultural movement that emerged to fill the vacuum in Irish life after the fall of Parnell in 1891 with a yearning to revive the traditions and customs of Ireland in an increasingly anglicised world. In the minds of Yeats and fellow revivalists, Ireland was besieged under the weight of Anglo-American modernity. He recognised a state of affairs that could only be reversed by committed cultural nationalism in the fields of arts and education. Whilst officially apolitical, the Gaelic Revival would act as an incubator for most of the future revolutionaries who would eventually sever formal British rule in Ireland and nurture the early Free State.

Despite

cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background

was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these

were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose

Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the

Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace

in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of

authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s

identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland

over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and

formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as

an artist as well as a man.

Despite

cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background

was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these

were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose

Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the

Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace

in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of

authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s

identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland

over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and

formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as

an artist as well as a man.

Yeats’s formal conversion to the cause of Irish separation came primarily through his relationship with the veteran Fenian John O’Leary, a minor member of the Young Irelanders. These were a group of mainly Trinity College based nationalists who split off from O’Connell’s Repeal movement. O’Leary had spent large tracts of his life in exile following the botched 1848 rebellion. Whilst abroad, he cultivated a distinctly cultured brand of Irish nationalism drawing not only on the recent traditions of the Young Irelanders but which also encompassed a wide range of influences stretching all the way back to classical antiquity. This form of nationalistic expression appealed very much to the twenty year old Yeats with its patriotic elements and emphasis on the individual in the shaping of history. Soon after his acquaintance with O’Leary, Yeats became a member of the fraternal organisation the Irish Republican Brotherhood, a secret oath bound group organised along semi-masonic lines counting the likes of Michael Collins and the leadership of the Easter Rising among their number and which played an often overlooked role in the securing of Irish freedom.

Whist being traditionally associated as a man of the right, Yeats did in fact rub shoulders with a group of left wing radicals in the form of the Socialist League, a bohemian group sympathetic to Irish nationalism and lead by the artist William Morris. The League attracted many Victorian artists to it’s ranks, including Oscar Wilde and Bernard Shaw. Though Yeats was sympathetic for a time to a form of socialism that would best promote the welfare of artists, he parted ways due to his disagreement with the “atheistic premises of Marxism” that the League embraced. Regardless of that, the League nurtured in Yeats a brand of politics that harboured respect for the individual within society, as well as furthering his disdain for the system of values of a decadent and increasingly mechanised England and the ascendant Catholic bourgeois in Ireland.

Despite

some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a

latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the

violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He

immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with

efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in

the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions

made to the arts. Despite his objection to anti-divorce legislation passed by the Free State and his defence of Republican prisoners, the writer Grattan Freyer

details how the poet’s primary gripe with the new state was a failure

to be sufficiently conservative, to cast off any trappings of liberalism

inherited from England, and embrace some sort of aristocratic order

(with Yeats no doubt playing a major role). In cabinet, he found

minister Kevin O’Higgins (photo) as a potential ally and was so aghast

at the young minister’s death at the hands of Republican gunmen that he

penned his poem “Blood And The Moon” a defence not only of the ailing world of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy to which he belonged, but also to the poet’s brand of conservative politics.

Despite

some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a

latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the

violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He

immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with

efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in

the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions

made to the arts. Despite his objection to anti-divorce legislation passed by the Free State and his defence of Republican prisoners, the writer Grattan Freyer

details how the poet’s primary gripe with the new state was a failure

to be sufficiently conservative, to cast off any trappings of liberalism

inherited from England, and embrace some sort of aristocratic order

(with Yeats no doubt playing a major role). In cabinet, he found

minister Kevin O’Higgins (photo) as a potential ally and was so aghast

at the young minister’s death at the hands of Republican gunmen that he

penned his poem “Blood And The Moon” a defence not only of the ailing world of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy to which he belonged, but also to the poet’s brand of conservative politics.

Yeats very famously had a bumbling relationship with the Blueshirts Ireland’s proto-fascist movement, which was born out of Treatyite politics and disgruntled farmers’ anger at De Valera’s trade war with the UK. There appears even to have been a ham-fisted attempt by Yeats to fashion the Blueshirts in his image with what one would imagine to be humorous attempts made to lecture Blueshirt leader Eoin O’Duffy on finer points about Hegel by the Nobel laureate, who did still script several marching tunes for the movement. Yeats’ anti-communism fitted naturally with an already conservative outlook of life and with his Burkean understanding that any utopian vision regarding the perfection of man and the trampling down of supposedly oppressive hierarchies, rested not merely on flimsy axioms but on an inevitable mound of corpses. Regardless to the extent of his involvement with Irish fascism this was to be Yeats’ final venture into the world of politics, with the poet largely withdrawing into artistic solitude in his final years. He had left a considerable mark on the Irish state and Irish people as a whole, even if today, their primary understanding doesn’t go beyond the handful of traditionally learnt poems of the Leaving Cert.

In an era when the Irish appear to be jettisoning any form of national distinctness retained after 700 years of colonisation in favour of the bum deal of cosmopolitanism, and with conservatives driftless in the shadow of a fallen Church, the potential use of Yeats as a cultural icon is attractive. Within this dynamic figure we see a man motivated by a sheer love of one’s own country as well as a desire to see a newly independent Ireland fashioning an identity from the richness of her traditions. There is not an iota of doubt that the poet would find himself at home in the embryonic conservative movement embodied in a journal such as this, and in similar movements across the western world which are at odds with the current order of affairs.

“We Irish, born into that ancient sect

But thrown upon this filthy modern tide

And by its formless spawning fury wrecked,

Climb to our proper dark, that we may trace

The lineaments of a plummet-measured face.” -The Statues by W.B. Yeats

Source

The political and cultural figures present in the early foundation of the Irish State present Irish liberals with some quandaries. Beneath the narrative of Irish independence being an inherently progressive movement betrayed by a post-Treaty “carnival of reaction”, lies an irreconcilable fact that the many of the figures driving separation from Britain belonged to a stridently conservative brand of thinking. Any budding conservative movement in Ireland should embrace these figures and cultivate a counter-narrative in response to the simplistic mistruths presented in works such as Ken Loach’s “Wind that Shakes the Barley”. Here, the Irish struggle is distilled down to a failed left wing revolt and those of a conservative inclination are portrayed as flagrantly unpatriotic and sometimes even at odds with Irish language revivalism.

The character of W.B. Yeats ranks perhaps first and foremost amongst those figures. Despite his Anglo-Irish background, he threw himself wholeheartedly behind not merely the political separation of his country from Britain, but the equally important task of forming a distinct Irish consciousness. First a political Tory committed to the cause of Irish freedom, he later became a reform-minded senator campaigning against the myopia of the Church-dominated Free State whilst simultaneously advocating for a more conservative state. Yeats, from the onset, strikes the modern reader as an enigma with his distinct brand of politics.

Yeats formed a central plank in what is now termed the Gaelic Revival, a cultural movement that emerged to fill the vacuum in Irish life after the fall of Parnell in 1891 with a yearning to revive the traditions and customs of Ireland in an increasingly anglicised world. In the minds of Yeats and fellow revivalists, Ireland was besieged under the weight of Anglo-American modernity. He recognised a state of affairs that could only be reversed by committed cultural nationalism in the fields of arts and education. Whilst officially apolitical, the Gaelic Revival would act as an incubator for most of the future revolutionaries who would eventually sever formal British rule in Ireland and nurture the early Free State.

Despite

cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background

was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these

were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose

Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the

Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace

in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of

authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s

identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland

over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and

formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as

an artist as well as a man.

Despite

cultural nativism being at its centre, Yeats’s Protestant background

was shared by most of the leading figures of the movement. Among these

were the Galway based aristocrat and folklorist Lady Gregory, whose

Coole Park home formed the nerve centre of the movement, and the

Rathfarnham born poet and playwright J.M. Synge, who later found solace

in Irish peasant culture on the western seaboard as being a vestige of

authentic Irish life amid a society of anglicisation. The poet’s

identification with both the people and the very landscape of Ireland

over the materialist England arose from his early childhood and

formative experiences in Sligo, a period that would define him both as

an artist as well as a man.Yeats’s formal conversion to the cause of Irish separation came primarily through his relationship with the veteran Fenian John O’Leary, a minor member of the Young Irelanders. These were a group of mainly Trinity College based nationalists who split off from O’Connell’s Repeal movement. O’Leary had spent large tracts of his life in exile following the botched 1848 rebellion. Whilst abroad, he cultivated a distinctly cultured brand of Irish nationalism drawing not only on the recent traditions of the Young Irelanders but which also encompassed a wide range of influences stretching all the way back to classical antiquity. This form of nationalistic expression appealed very much to the twenty year old Yeats with its patriotic elements and emphasis on the individual in the shaping of history. Soon after his acquaintance with O’Leary, Yeats became a member of the fraternal organisation the Irish Republican Brotherhood, a secret oath bound group organised along semi-masonic lines counting the likes of Michael Collins and the leadership of the Easter Rising among their number and which played an often overlooked role in the securing of Irish freedom.

Whist being traditionally associated as a man of the right, Yeats did in fact rub shoulders with a group of left wing radicals in the form of the Socialist League, a bohemian group sympathetic to Irish nationalism and lead by the artist William Morris. The League attracted many Victorian artists to it’s ranks, including Oscar Wilde and Bernard Shaw. Though Yeats was sympathetic for a time to a form of socialism that would best promote the welfare of artists, he parted ways due to his disagreement with the “atheistic premises of Marxism” that the League embraced. Regardless of that, the League nurtured in Yeats a brand of politics that harboured respect for the individual within society, as well as furthering his disdain for the system of values of a decadent and increasingly mechanised England and the ascendant Catholic bourgeois in Ireland.

Despite

some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a

latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the

violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He

immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with

efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in

the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions

made to the arts. Despite his objection to anti-divorce legislation passed by the Free State and his defence of Republican prisoners, the writer Grattan Freyer

details how the poet’s primary gripe with the new state was a failure

to be sufficiently conservative, to cast off any trappings of liberalism

inherited from England, and embrace some sort of aristocratic order

(with Yeats no doubt playing a major role). In cabinet, he found

minister Kevin O’Higgins (photo) as a potential ally and was so aghast

at the young minister’s death at the hands of Republican gunmen that he

penned his poem “Blood And The Moon” a defence not only of the ailing world of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy to which he belonged, but also to the poet’s brand of conservative politics.

Despite

some apprehension about the nature of the Easter Rising, as well as a

latent sense of guilt that his work had inspired a good deal of the

violence, Yeats took a dignified place within the Irish Seanad. He

immediately began to orientate the Free State towards his ideals with

efforts made to craft a unique form of symbolism for the new State in

the form of currency, the short lived Tailteann Games and provisions

made to the arts. Despite his objection to anti-divorce legislation passed by the Free State and his defence of Republican prisoners, the writer Grattan Freyer

details how the poet’s primary gripe with the new state was a failure

to be sufficiently conservative, to cast off any trappings of liberalism

inherited from England, and embrace some sort of aristocratic order

(with Yeats no doubt playing a major role). In cabinet, he found

minister Kevin O’Higgins (photo) as a potential ally and was so aghast

at the young minister’s death at the hands of Republican gunmen that he

penned his poem “Blood And The Moon” a defence not only of the ailing world of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy to which he belonged, but also to the poet’s brand of conservative politics.Yeats very famously had a bumbling relationship with the Blueshirts Ireland’s proto-fascist movement, which was born out of Treatyite politics and disgruntled farmers’ anger at De Valera’s trade war with the UK. There appears even to have been a ham-fisted attempt by Yeats to fashion the Blueshirts in his image with what one would imagine to be humorous attempts made to lecture Blueshirt leader Eoin O’Duffy on finer points about Hegel by the Nobel laureate, who did still script several marching tunes for the movement. Yeats’ anti-communism fitted naturally with an already conservative outlook of life and with his Burkean understanding that any utopian vision regarding the perfection of man and the trampling down of supposedly oppressive hierarchies, rested not merely on flimsy axioms but on an inevitable mound of corpses. Regardless to the extent of his involvement with Irish fascism this was to be Yeats’ final venture into the world of politics, with the poet largely withdrawing into artistic solitude in his final years. He had left a considerable mark on the Irish state and Irish people as a whole, even if today, their primary understanding doesn’t go beyond the handful of traditionally learnt poems of the Leaving Cert.

In an era when the Irish appear to be jettisoning any form of national distinctness retained after 700 years of colonisation in favour of the bum deal of cosmopolitanism, and with conservatives driftless in the shadow of a fallen Church, the potential use of Yeats as a cultural icon is attractive. Within this dynamic figure we see a man motivated by a sheer love of one’s own country as well as a desire to see a newly independent Ireland fashioning an identity from the richness of her traditions. There is not an iota of doubt that the poet would find himself at home in the embryonic conservative movement embodied in a journal such as this, and in similar movements across the western world which are at odds with the current order of affairs.

“We Irish, born into that ancient sect

But thrown upon this filthy modern tide

And by its formless spawning fury wrecked,

Climb to our proper dark, that we may trace

The lineaments of a plummet-measured face.” -The Statues by W.B. Yeats

Source